Upon moving to Pittsburgh in 2007, I heard that the mayor of Braddock was giving free studio space to artists. Although it sounded too good to be true, I was able to acquire a rent-free studio space in the Ohringer Building. It was admittedly a dark, scary place with little ventilation or lighting (an elevator without lights is very creepy), and lots of plumbing issues. And if I found myself there past sundown, I would half run to my car to avoid unwanted encounters. But all that mattered to me was that I had a free space to make work.

The Ohringer Building project was implemented by John Fetterman, the Mayor of Braddock, to determine whether or not people, specifically artists, would come to Braddock. Now known as Braddock Redux, the mission was to create centers of community activities involving many different groups of people. By transforming these spaces into studios, the owners of the building, Braddock Redux, received a grant to renovate the building. Soon after the project began the building was full; thirty artists occupying spaces and a wait-list of thirty or more. This particular site was short lived, but it provided evidence that if properly enticed, people would go to Braddock.

But what about the families that have been living in Braddock for generations? How would a couple dozen artists commuting into their town help out the area as a whole? The population of Braddock has dwindled to around 2,000 residents; a 90% decline from the 1950’s. Basic services have disappeared. There is no longer a hospital; in 2010 UPMC relocated to a new building in a more affluent suburb in Pittsburgh.

It’s ironic that a community such as Braddock doesn’t have access to medical facilities given that a very high percentage of its residents suffer from one or more pollution-borne ailments. Frazier herself has lupus, an immune system disease. The main culprit of this toxic environment polluting the land for over a century is the steel industry. Andrew Carnegie’s first steel mill built in 1872 is Braddock’s largest employer. Still in operation, not one of their current employees calls Braddock home.

These are the difficult concerns that LaToya Ruby Frazier asks us to consider in “Born by a River” currently on view at the Seattle Art Museum. At 31, Frazier is the third recipient of SAM’s biannual Gwendolyn Knight/Jacob Lawrence Prize; a prestigious award that goes to black artists whose exhibition history does not extend beyond 10 years and which provides them with funding and a museum exhibition. Her exhibition includes photographs, accompanied by video footage of Frazier explaining the history and unique plight of Braddock. She explains how it has affected her family and shaped her work since childhood.

I don’t think it’s a surprise to see a show surrounding this content in a city like Seattle and “Born by a River” can inform viewers in valuable way. The stark reality of Braddock is not something Seattle is experiencing first hand. With the thriving economy in Seattle, buildings and homes are going up faster than I can believe. Ideas of poverty and long standing environment-defiling industry don’t exist here like they do in a place such as Braddock. And you can’t rely on the media to get at the reality of Braddock like Frazier’s photographs do.

In the main room of the gallery are seven large color photographs taken from a helicopter, showing aerial perspectives of Braddock.

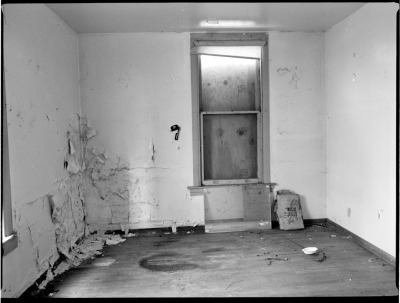

These contrast with smaller-sized black and white photographs of dilapidated buildings taken at ground level. Outside the main gallery are two dozen portraits of Frazier and her family – who have lived in Braddock for three generations.

The aerial photographs show something that I’m not familiar with in my memory of Braddock. Driving through, I was usually in a daze of fascination that people actually live in houses barely standing, with boarded-up windows and caved-in roofs.

The aerial photographs by Frazier make Braddock seem beautiful and logical in a mathematical way, from way up high. There are no people in the photographs, which lend eeriness to them, if not a peaceful quality.

Contrary to this, when you are actually walking through Braddock with the hum of the mill in the background and the off-smell in the air, you get an entirely different experience. The exhibit polishes up the reality of Braddock. From the slickness of the medium of photography to the beautiful, clean frames around them, there’s a certain glamour to these images.

Looking at the family photos, especially the ones including Frazier’s grandmother surrounded by her doll collection, this mundane occasion gets elevated to something else. While being fascinated by the family photos, you do feel the sadness of disease and poverty existing in their lives.

These photos also show people that depend on one another to survive. When I used to think about the kind of family life inside these decaying houses, I expected to see something different than what the photos show. I expected to see a life not worth living. Without seeing it firsthand from the inside, my references come from the media or television, which tend to portray a life in Braddock as a hopeless existence. That is why these photographs are so pertinent to understanding a place that people see as all bad all of the time. If you take the details of the work Frazier presents us and piece them together, you begin to experience something different that is invisible in mainstream media, something closer to the truth.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Born By a River is on view at the Seattle Art Museum, December 13, 2013–June 22, 2014.

Rob Katkowski is a painter and picture framer living in Seattle, WA. He received his MFA in Painting from Edinboro University of Pennsylvania in 2007.